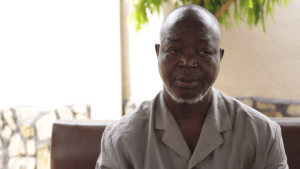

For over two decades, Luke Atinga has tilled the soil in the Bolgatanga Municipality of Ghana’s Upper East Region. Like many smallholder farmers in the country, his livelihood has been shaped, in part, by successive government agricultural interventions.

From fertilizer subsidies to training programs, Atinga has always found a way to participate—sometimes by registering with cooperatives, other times through the district agricultural office, and occasionally when government officials came directly to his farm.

But in 2023, everything changed. The Akufo-Addo administration had announced a bold new phase of the government’s flagship agricultural programme, Planting for Food and Jobs (PFJ). Dubbed PFJ 2.0, the new version came with enhanced ambitions and a critical new requirement: registration through the Ghana Card.

For Atinga, who had not yet acquired his Ghana Card, this meant he was automatically excluded. For the first time in his farming life, he could not benefit from a government initiative.

PFJ 2.0: A New Vision for Ghana’s Agriculture

With food insecurity on the rise and the cost of agricultural inputs mounting, the government under President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo introduced PFJ 2.0 as a radical upgrade of the original 2017 policy.

Unlike the earlier phase, which largely provided input subsidies, PFJ 2.0 aimed for a complete transformation of the agricultural value chain. The program moved from a supply-driven model to a demand-driven system with the farmer at the core of its design.

Central to this vision was the Ghana Agricultural and Agribusiness Platform (GAAP)—a digital infrastructure intended to register farmers, map farmland, track production, and ensure transparency. PFJ 2.0 connected producers with aggregators, processors, marketers, and financial institutions in a streamlined ecosystem.

What set this phase apart was the mandatory use of the Ghana Card. By leveraging the national biometric ID, the program sought to eliminate ghost names, ensure accurate data capture, and enhance traceability. Each farmer’s profile—complete with farm size, location, and crop type—could now be monitored in real time. But this digital leap, while groundbreaking, also introduced new layers of complexity.

How the Registration Process Worked

Once farmers submitted their biometric details—verified through the Ghana Card—Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MoFA) officials would follow up to verify farm locations. Using digital tablets, officials would map out each parcel of land, logging the GPS coordinates and tying them to the farmer’s personal data.

This mapping exercise ensured that no farmer could register multiple times, even in different regions or with another Ghana Card. It was an innovation that brought data integrity to the heart of agricultural planning.

What Went Right: Eliminating Ghost Names and Duplicates

Thomas Akun, the Upper East Regional Director of the Department of Food and Agriculture in charge of Extension Services, praised the robustness of the GAAP system. He emphasized that tying registration to both biometric data and geolocation greatly reduced fraud.

“The system was so strong that if you registered once, you wouldn’t be able to register again—even in a different region with a different Ghana card. It flagged duplicates instantly,” he said.

Akun believes that the data infrastructure created under PFJ 2.0 should not be discarded.

“We pray that any intervention or policy coming to support farmers can build on this data. We can improve it and continue using it.”

His sentiments were echoed by Alhaji Fuseini Zakaria, the Upper East Regional Director in charge of Food and Agriculture, who added:

“When we didn’t use biometric data, we saw a lot of duplicate names. The Ghana Card was the right approach.”

What Didn’t Work: Technology Gaps and Access Barriers

Despite the technological advancements, several operational hurdles surfaced. The first challenge was the shortage of registration devices. Some districts received only four tablets, even though they had more than ten extension officers. This created bottlenecks, delayed registrations, and left some farmers out.

Connectivity was another issue. Poor internet access in rural areas meant that fieldwork was often delayed or disrupted.

“Sometimes you’d be out in the field and there’d be no network at all,” Mr. Akun explained.

A more serious problem was the inaccessibility of the Ghana Card itself. Many farmers did not have it, and those who did were sometimes hesitant to share their data due to privacy concerns.

“Especially those who were enlightened a bit, they didn’t want to share their personal data. They were concerned about how it would be used,” Akun added.

Moreover, logistical difficulties also emerged. Some farmers lived far from their actual farmland. This meant that registration teams had to travel significant distances just to map each plot—a time-consuming and expensive endeavor.

Farmer Frustrations: Lost Opportunities Due to Tech Glitches

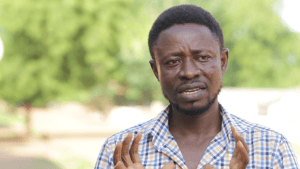

Farmers like Adombilla from Yikene faced even more technical challenges. Though he had a Ghana Card and was eager to participate, the registration system could not validate his ID. Despite his insistence that he hadn’t used the card elsewhere, he was locked out—and registration closed before the issue could be resolved.

Linda Nosbila had a similar experience. Her Ghana Card had worked flawlessly in the past, but during the PFJ 2.0 registration, the system failed to recognize it. She too lost her chance to benefit from the program.

Enter ‘Feed Ghana’: A New Era, a New Approach

The current administration under President John Dramani Mahama has replaced PFJ 2.0 with a new initiative: Feed Ghana. While the Ghana Card remains central to registration, officials are now adapting to past challenges.

Peter Nuhu, Coordinator of the Farmer Services Centres, confirmed that the system is being made more flexible. Under Feed Ghana, farmers like Adombilla and Linda will be registered, even if there are card issues.

“MoFA will liaise with the National Identification Authority to resolve discrepancies so that no willing farmer is left behind,” he assured.

The Ghana Card Debate: Promise vs. Reality

Tech expert and CEO of Norgence, Albert Naa, agrees that the use of the Ghana Card is a “master stroke” for cleaning data and promoting inclusion. But he questions the wisdom of using it as the sole registration tool when many rural farmers still lack access.

“Before tying such important services to the Ghana Card, the government should’ve ensured that farmers could access the card easily,” he cautioned.

His concern echoes what many field officers and farmers experienced: the technology was sound, but the groundwork was incomplete.

Conclusion: Bridging the Gap Between Innovation and Inclusion

The story of PFJ 2.0 is a reflection of Ghana’s broader attempt to modernize agriculture through technology and data. It was ambitious, timely, and offered a glimpse into the future of farming. But the experience of farmers like Luke Atinga, Adombilla, and Linda reminds us that good policy must be matched by inclusive implementation.

As Ghana moves into the Feed Ghana era, the challenge remains the same: to build a system that is technologically robust yet socially responsive—where no farmer is left out because of a card they don’t have, or a system that won’t let them in.

“This report is produced under the DPI Africa Journalism Fellowship Programme of the Media Foundation for West Africa and Co-Develop.”

Source: A1Radioonline.com|101.1Mhz|Mark Kwasi Ahumah Smith|Bolgatanga