Adeeza’s breaths came in short, rapid bursts. As the bus rumbled from Bolgatanga toward Accra each inhalation felt like fire in her lungs. For the asthma patient, these moments signaled mortal danger — her body screaming that something was triggering her compromised respiratory system.

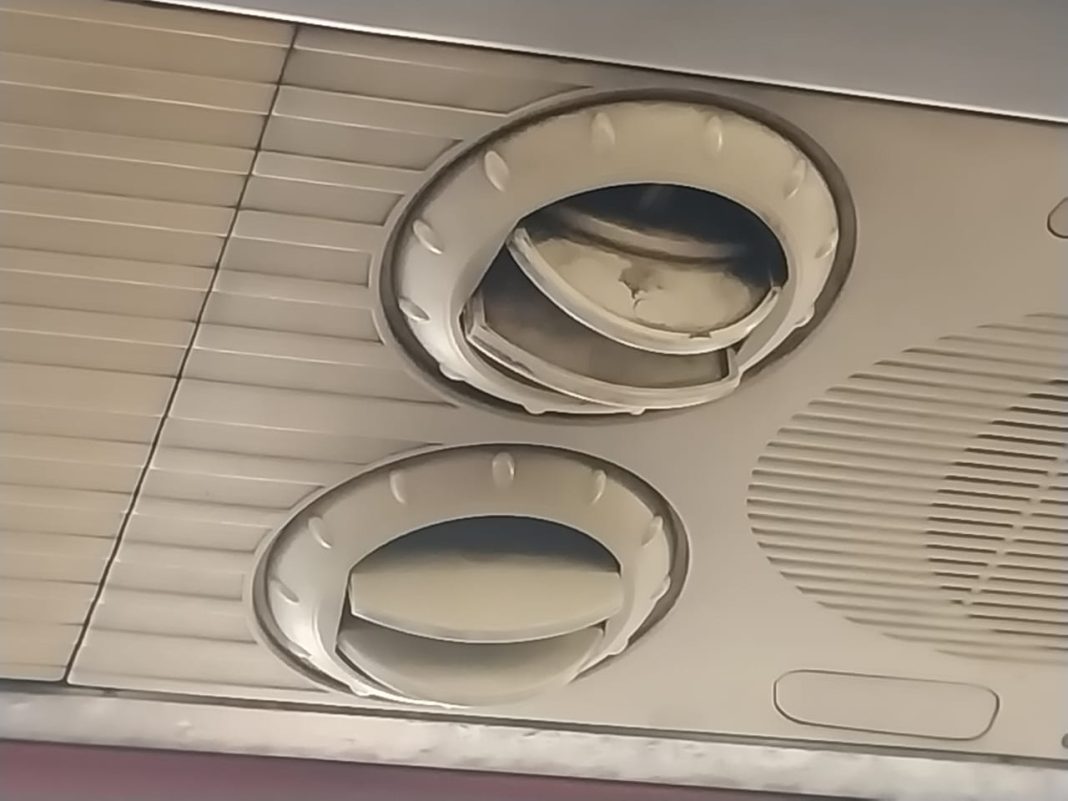

Adeeza scanned the bus, desperately searching for the regular culprits. Strong perfume? She could not detect any. Excessive dust from outside? The windows were shut. She ran her finger lightly across the opened air-conditioning vent above her seat. What she found shocked her.

“It was actual sand,” she recalled in an interview. The vent that was supposed to circulate cool, clean air throughout the 15-hour journey had instead become a repository of filth, spewing particles directly into passengers’ lungs.

“I felt like I was dying,” Adeeza said. “These attacks are not something to joke with.”

Adeeza was lucky that time. She left the bus and recovered. But her experience reflects what experts said is a largely overlooked health crisis in Ghana: dangerous air quality inside long-distance buses, with poorly maintained air-conditioning systems, has transformed vehicles into mobile chambers of poisoned air. As Ghana grapples with a growing air pollution crisis that claimed over 32,000 lives in 2023 — the air inside its buses remains unregulated, uninspected and, for passengers like Adeeza, potentially lethal.

Experts say the scale of exposure is staggering. On the Bolgatanga-to-Accra route alone, transport operators estimate that over 153,000 passengers travel annually. Private companies like VIP and OA Travel and Tours each transport roughly 25,000 passengers per year on this single route, while stations operated by the Ghana Private Road Transport Union in Bolgatanga, Bawku, Garu and Zebilla collectively move more than 102,000 passengers. Across Ghana’s extensive network of long-distance routes, millions of trips are taken each year, with passengers spending anywhere from eight to 18 hours in enclosed buses.

The problem begins with neglect. Francis Enyan, who drives the Bolgatanga-to-Accra route, said he services his bus every four trips — changing the oil and attending to general maintenance needs. But the air-conditioning system, filters and ducts follow a different schedule: They are serviced only when something goes wrong.

“For the air-conditioning side, it is the driver who should check whether the bus is cooling enough for passengers or not, then you will decide to work on it,” Mr. Enyan said in Twi. He said air quality never factors into maintenance decisions. The cooling system is checked only when temperatures rise, not when the filters clog with dust, when mold colonizes the vents, or when bacteria find breeding grounds in the moisture-laden coils.

According to Mr. Enyan, the process is simple when problems arise: Washing bay attendants use high-powered guns to blow dust off the top of the bus, where large fans circulate cold air. Air-conditioning mechanics handle the rest. But by then, passengers may have already spent hours inhaling whatever accumulated inside.

And that can be deadly.

“Definitely any journey, at least more than six hours in that condition, is very harmful to the passengers or to the inhabitants of the bus,” said Dr Aaron Tetteh, a medical officer at the Upper East Regional Hospital. The danger lies in what accumulates inside the air-conditioning system according to Dr Abdul Muizz Muktar, a lecturer in environmental and occupational health at the University for Development Studies. Filters trap dust, mold and bacteria from the environment. When cleaned regularly, the system protects passengers. When neglected, it does the opposite.

“If they are unclean, you would see that when they accumulate, the air conditioner is likely to release excess of this dust, among other contaminants, back into the room or into the car,” Dr Muktar said. In the humid environment of an air-conditioned bus, these contaminants don’t simply sit idle. “It is a place for the reproduction of some of the pathogenic bacteria that may be trapped in there.”

The dangers multiply with time. While short-distance vehicles may expose passengers to negligible amounts, long-distance travel prolongs exposure. What circulates through the vents isn’t just household dust but “a concentration of dangerous bacteria, viruses and other dust mites and allergens,” Dr Muktar said. Passengers may develop infections, respiratory diseases or severe allergic reactions. For vulnerable populations — children, the elderly and those with underlying conditions like asthma — the consequences can be catastrophic.

No studies have been done on the air quality levels in Ghana’s long distance buses but research in other countries shows how bad things can get. In Costa Rica and New Zealand researchers found carbon dioxide levels inside buses rising as high as 5,000 parts per million and 3,440 p.p.m. respectively — clear indicators of dangerously poor ventilation. The World Health Organization recommends keeping carbon dioxide levels below 1,000 p.p.m. for healthy indoor air quality.

Experts said without data from Ghana’s buses, passengers, health officials and policymakers do not know the full extent of the crisis. But they said they have no doubt it is severe.

Modesta Adongo experienced this firsthand during a last-minute trip from Accra to Bolgatanga. Unable to secure a ticket with her usual transport company, she boarded a random bus at the Neoplan station. The vehicle looked questionable from outside, but what she discovered inside horrified her.

“If you looked at where the air-conditioning comes from, it is like it was leaking and it was not fixed early, so there was some black thing looking like algae in the corners of the vents,” she said. At nearby seats she found the same black substance — what experts identify as mold — surrounding every vent. “I was asking, is this what we are breathing?”

As air quality deteriorates, oxygen levels decrease and carbon dioxide accumulates, according to Dr Tetteh. Passengers become fatigued. They cough. They sneeze. Headaches develop. Some run fevers. For asthma patients and those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, the contaminated air can trigger acute attacks.

Ghanaian law offers passengers little formal protection. No Ghanaian law directly addresses air quality in long-distance buses. After consulting with headquarters, John Quarshie, the Upper East regional public relations officer for the National Road Safety Authority pointed to Section 13(a) of the National Road Safety Authority Act, which expects operators to “comply with safety standards established by the Authority or any other relevant authority.” That vague provision, combined with public health safety regulations, offers the only guidance.

The regulatory gap leaves passengers to protect themselves. Mr. Muktar recommended personal protective equipment, particularly N95 masks, which filter out dust, mold spores and other contaminants. He advised avoiding seats directly beneath air-conditioning vents, where exposure is most concentrated. Passengers should ask drivers to reduce fan speed if the air smells moldy or request that windows be opened slightly to dilute contaminated air — though drivers often resist such requests.

Dr Tetteh said hydration was crucial for managing exposure. “Anytime you are not well hydrated, all those particles, they tend to worsen whatever symptoms that you are feeling,” he said. He recommends N95 masks specifically for their built-in ventilation and advises passengers to exit the bus during stops to breathe fresh air.

For Adeeza, the solution came from her nurse, Jerome Anaane, a family clinician who had previously advised her to avoid dusty environments and strong perfumes. After the bus incident, his recommendations changed. “Since that attack, I have directed that her nose mask is always on, especially in the buses for when she travels,” he said. Before that journey, contaminated air-conditioning vents hadn’t been a consideration in managing her asthma. Now it’s a primary concern.

The broader context makes the situation more urgent. Experts say air pollution claimed over 32,000 lives in Ghana in 2023, accounting for nearly 14 percent of all deaths and establishing air pollution as the nation’s second-leading risk factor for death, behind only high blood pressure. Household air pollution from burning wood, charcoal and other solid fuels accounts for 71 percent of pollution-related deaths, while outdoor particulate matter accounts for 29 percent.

But the air inside long-distance buses — where passengers spend 15 hours or more in enclosed spaces — remains a minefield.

Dr. Muktar would like comprehensive policy reform: mandatory air-conditioning maintenance standards with scheduled filter cleaning and replacement, similar to road readiness certifications.

“Just as we have a mandatory road readiness certification, as part of road readiness certification, they can also put in the mandatory air conditioner system servicing and maintenance,” he said.

He also suggested periodic air quality testing at checkpoints, measuring PM 2.5 and PM 10 levels — the particulate matter most harmful to human health. Enforcement would require coordination among road safety authorities, the Environmental Protection Agency and public health departments. Buses could display tags indicating when air-conditioning systems were last serviced, allowing passengers to make informed decisions.

He also suggested tax incentives for operators who maintain clean air standards, regulations prohibiting buses from idling for extended periods and digital monitoring systems that alert passengers and drivers when pollutant levels exceed safe thresholds.

“These are all things that government can put in place,” Dr. Muktar said.

Experts said the need for such protections grows more urgent as bus travel remains the most affordable and convenient option for millions of Ghanaians traveling between regions. Without private vehicles, they have little choice but to board buses like the one that nearly killed Adeeza, where the air they breathe during their journeys may be slowly destroying their health.

For now, passengers like Ms. Adongo have adapted by taking precautions into their own hands — wearing masks, choosing their transport companies carefully and hoping that the air circulating above their heads won’t make them the next statistic in Ghana’s growing air pollution crisis.

This story was a collaboration with New Narratives as part of the Clean Air Reporting Project. Funding was provided by the Clean Air Fund. The donor had no say in the story’s content.

Source: A1 Radio | 101.1Mhz| Mark Kwasi Ahumah Smith | Bolgatanga

Dr. Abdul Muizz Muktar – UDS

Dr. Abdul Muizz Muktar – UDS

John Quarshie, NRSA

John Quarshie, NRSA N95 Nose mask

N95 Nose mask