One Saturday afternoon in New York City, several decades ago, a young Ghanaian student sat alone in his dorm room at 362 Riverside Drive, hungry, broke, and uncertain of what the next hour held.

He didn’t even have a dime to make a phone call. In those days, that would have been enough to reach someone on the payphone; in this case, a friend.

Had he been able to call his friend, he would’ve confessed how empty his pockets were, and how the only thing left in his fridge was half a bottle of ketchup. Not even a slice of bread to go with it.

With nothing to eat and no solution in sight, he decided to leave the room and walk down the six flights of stairs, just to take his mind off the gnawing hunger. At the lobby, the building’s Afghan doorman spotted him. “You! Come here!” he barked. Reluctantly, he approached. The man handed him an envelope. “You get letter here,” he said. It was unexpected, he hadn’t imagined he’d receive anything that day, much less something that could change everything.

Inside was a letter from City College, where he’d been working part-time at the library. Folded within it was a cheque for $170. He stared at it, stunned. His stomach, moments ago aching with emptiness, now fluttered with disbelief and joy. Without wasting time, he dashed out and bought a full chicken, potatoes, and a six-pack [of beer]; everything he had craved but couldn’t afford just an hour before.

That broke student would one day become one of Africa’s fiercest defenders of press freedom; a relentless advocate for truth and the power of the media.

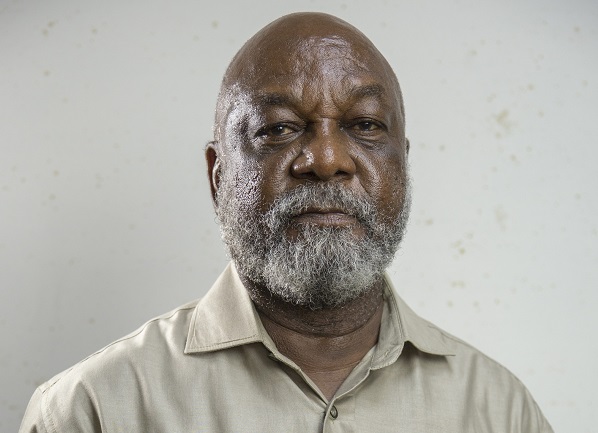

Professor Kwame Karikari

Born in Tamale, in what was then the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast, Kwame Karikari was raised by a quiet, soft-spoken father; a clerk with the British wartime Garrison Engineers—and a strong-willed, justice-driven mother. His worldview, shaped early on, was a fusion of his mother’s courage and defiance and his father’s patience, honesty, and humility.

He started school at Presbyterian Middle School, known for its Spartan discipline, before advancing to Komenda Teacher Training College, where Christian values were enforced more through farm work than punishment. It was there that his love for writing took root, nurtured by contributions to the school’s student newsletter.

But the seeds of journalism had been planted even earlier. As a child, he read newspapers aloud to his aunt, a woman he so admired that he would later name his daughter after her. He also vividly recalled seeing Kwame Nkrumah twice—formative moments that steered his ideological compass toward Pan-Africanism and socialism.

After earning a Teacher’s Certificate ‘A’ and a diploma in history from the Advanced Teacher Training College in Winneba, then located in the old Kwame Nkrumah Ideological Institute, he taught at Navrongo Secondary School. It was there, in the library, that he discovered Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth, a text that deepened his understanding of justice and liberation.

Even outside the classroom, he gave himself fully to service, volunteering with the Voluntary Work Camps Association and traveling across Ghana during holidays to work on community development projects. When he eventually left for the United States in his 20s, it wasn’t to escape, but to prepare himself to serve better.

A Ghanaian in New York: Activism, Journalism, and Identity

He arrived in New York intending to study journalism at Columbia University. But the city, and the times, had other lessons in store. It was the 1970s: civil rights, anti-war protests, Black Power, and African liberation movements filled the streets and classrooms.

Immersed in this electric atmosphere, he co-founded the African Youth Movement for Liberation and Unity, aligning with global struggles against dictatorship and injustice. His academic path took him through City College and later Columbia, but just as important was his work with The Paper, a Black student publication where he sharpened his political voice.

He later wrote for and edited progressive publications like Augusta Weekly and The Guardian Weekly, gaining deeper insights into Black life in the American South and resistance movements around the world. But Ghana was never far from his heart. When the University of Ghana launched its School of Communication, he returned at 34, stepping into a Ghana still reeling from the June 4th uprising.

From that point on, his life and Ghana’s story became tightly intertwined.

Politics, Jail, Jerry John Rawlings and everything in between.

It was 1979. Professor Karikari had returned from New York, and not long after, another young Ghanaian, this one back from Europe, also arrived. Their paths crossed in the heat of national upheaval, with three governments rising and falling in the space of a year.

Amid the chaos, a friendship quietly formed. Two thinkers drawn together by a shared resistance to authoritarianism and a deep commitment to justice.

“Kwame became my reference point,” Dr. Yao Graham would later say. “Not just as a friend, but as a comrade.”

Their politics were never about party colors or self-interest. It was always about people—about justice that went beyond legalese into the lived experiences of Ghanaians.

As Dr. Graham recalled, democracy for his friend wasn’t just about elections and slogans, but about substantive equality. “The law frames equal rights,” he explained, “yet, we still live lives of inequality.”

For them, the struggle wasn’t abstract, it was rooted in communities, in resisting the commodification of participation, and in empowering citizens to shape their own realities. This is why the New Democratic Movement (NDM), which they co-founded, was so pivotal. It wasn’t just a political organization; it was a lifeline to a vision of Ghana in which the poor were more than just voters—they were the architects of their own future.

That vision, however, came at a cost. Under Rawlings’ military regime, their resistance to neoliberal policies and authoritarian drift led to their arrest. Professor Kwame Karikari spent 18 months in political detention without trial, an experience that would have broken many.

But it only deepened his convictions. He emerged with even greater clarity about the kind of democracy he believed in: one built not on spectacle, but on structure, where power is not performed but shared. As Dr. Graham put it, “We saw that the regime had turned against the interests of ordinary people.”

And so they resisted, again.

Speaking at a public lecture organised in honour of Professor Kwame Karikari’s 80th birthday, Dr. Graham said “As we honour him today, we must also confront the unfinished work he spent his life pursuing.”

“This is a country celebrated as a model of democracy,” Dr. Graham said. “Yet, 4.8 million Ghanaians live in slums.”

According to Dr. Graham, they are not just statistics; they are indictments. They are the very gaps Professor Karikari spent decades trying to close, through media freedom, civic education, and grassroots mobilization.

Lecturing, University of Ghana and Mentoring

If Professor Kwame Karikari’s life had been a masterclass in activism, then to those who knew and worked with him closely, it was also a lesson in mentorship, humility, and institution building.

“We’re not only celebrating a champion of press freedom, human rights, and democracy,” Professor Audrey Gadzekpo said, sitting before a packed audience in his honour. “We’re also honoring an educator, a mentor, an institution builder, embodied in one remarkable man.”

Over three decades ago, he had offered her a teaching position at the School of Communication Studies, where he had already become a towering figure. “He mentored not just faculty, but staff—and students too,” she recalled. He forged partnerships far beyond the walls of academia, connecting classrooms to newsrooms, theory to practice, and passion to policy. Under his leadership, the school’s influence grew, its curriculum deepened, and its reach extended far beyond Legon’s gates.

Professor Gadzekpo spoke of a man who did not see contradiction in wearing multiple hats: academic, activist, strategist, and friend. From convening the first national conversations on the privatization of broadcasting to helping draft Ghana’s first journalists’ code of ethics, his interventions were never abstract.

They shaped the foundation of media ethics and law during Ghana’s fragile transition to democracy. When tensions rose, as they once did during an inspection of the campus radio station, he met them with his trademark blend of calm, wit, and conviction.

Even in retirement, Professor Karikari defied rest. He continued building journalism programs, training journalists across post-conflict and authoritarian states, from Rwanda and Eritrea to Liberia and Sudan.

“He seemed to gain a second wind,” she laughed, “but that’s one part of his legacy I refuse to emulate!”

Yet she made it clear that as friends, family and partners celebrate him, they must also confront the challenges he warned about: a declining global press freedom index, the corrosive effect of media capture, and the encroaching risks of AI-driven misinformation.

“In Kwame, we find a model for how to meet these challenges, with courage, scholarship, activism, and humility,” she said, with hope.

The Media Foundation for West Africa

Femi Falana, the Nigerian human rights lawyer whose own name is etched in the annals of West Africa’s democratic struggles, rose to deliver the keynote address.

A figure forged in the fires of courtroom battles and street protests, Falana did not offer bland praise or abstract ideals. He spoke, as he always does, with clarity.

“When we identify a few good people in the midst of criminals all over the world,” he declared, voice cutting through the laughter that had engulfed the hall, “we must celebrate them.”

That, he said, was why they had gathered, to celebrate not simply a scholar or a professional, but a man who had become, for many, the moral infrastructure of media freedom in Africa.

He recalled standing trial for treason before a Nigerian military tribunal, an absurdity, he noted, given that those truly guilty of subverting the constitution were seated in the presidential villa. “This law on treason was not meant to protect dictators,” he argued in court, invoking a clarity of legal logic that has long been his hallmark. But his purpose in this moment was not to relive his own trials; it was to remind the audience that people like Prof. Kwame Karikari had stood by activists, journalists, and exiled voices, not as an observer, but as a participant, a builder, a shield.

Falana detailed the work of the Media Foundation for West Africa under Karikari’s stewardship: challenging despotism in Gambia through the ECOWAS Court, representing tortured journalists, securing landmark rulings, and even uncovering the tragic reality that some disappeared before justice could reach them. “The Prof came to give evidence in court,” Falana recalled, “and his oral testimony convinced the judges that justice had to be done.”

And when the judgments came—$100,000 for Embrima Manneh, $200,000 for Musa Saidykhan, and a long-delayed reckoning for Deyda Hydara’s murder—Karikari was not just behind the scenes. He was often the one pushing reluctant systems forward, urging lawyers to act, demanding accountability long after headlines had faded. He helped transform silence into sentences—into law, redress, and remembrance.

Falana’s tribute spanned courtrooms and countries, dictatorships and democratic openings, always returning to one unwavering theme: Karikari’s insistence that freedom of expression is not a luxury for elites or a borrowed Western ideal. “It is,” he said, “a fundamental essential for human dignity.”

From mentoring young reporters to challenging predatory development models, from defending local language journalism to fighting imperial misinformation, Professor Karikari’s work, Falana emphasized, was both global and granular. He wasn’t merely a professor, he was a public intellectual in the radical tradition, where knowledge is forged into tools, and courage is measured by how deeply one is willing to risk comfort for conscience.

“He is,” Falana concluded, “not just a name in African media history. He is a living embodiment of civic courage. A call to action.”

Hope for the future

Professor Karikari, the last to speak, spoke not with self-congratulation, but with deep gratitude and an enduring faith in the future. He brought his granddaughter forward, his “little girl,” as he called her, to stand beside him as he reflected on the journey still ahead. “I have faith in the future,” he said gently, “faith in our continent, our people, our country.”

That faith, he explained, was rooted in the energy of the young, in the tenacity of a new generation of thinkers, builders, and justice-seekers. From the early days of arrest and activism to the founding of the Media Foundation for West Africa, he saw the baton being passed—not to an institution alone, but to a living movement committed to media freedom, public accountability, and democratic ideals. “I played my part,” he said, smiling. “Now they play theirs.”

He named comrades who stood by him through struggle and reform, men and women who challenged systems and imagined a freer world. Some had walked with him through prisons and picket lines; others now led universities, civil society spaces, or quietly transformed lives in their own corners.

For Karikari, progress would not come from the top down, but from communities rising together with clarity, courage, and collective purpose.

In the end, it wasn’t titles or tributes that stirred him. It was the sight of former students, exiled journalists, old friends and new allies, gathered with laughter and love. “This whole thing, this exaggeration of who I am,” he said with a soft chuckle, “I’ve been cooked by good people.”

But even in jest, the call was clear: the work is not finished, the future is calling, and all seated in the hall, were invited to shape it.

“God dey,” he said.

Source: A1radioonline.com|101.1MHz|Mark Kwasi Ahumah Smith|Ghana