Summary

- More than 95 percent of Ghana’s freight is moved by diesel trucks, exposing millions of people along major highways to dangerous air pollution linked to respiratory disease and early death.

- Successive governments have promised to revive freight rail, but decades of underinvestment and stalled projects have left rail carrying less than 1 percent of the country’s cargo

- Experts say shifting freight from roads to rail could sharply cut pollution, reduce road damage and save lives, but warn that without urgent action the health and climate costs will keep rising

By Mark Kwasi Ahumah Smith

BALUNGU CHECKPOINT, Upper East Region – Abdul Malik eases his heavy truck – a 12-wheel trailer hauling a 40-foot container – into a lower gear as it strains under its load. As he approaches this checkpoint in the region’s Talensi District, the roar of the 18-year-old truck’s engine gives way to thick plumes of black smoke billowing from the exhaust. Inside the cab fumes seep through every gap, coating surfaces in soot and filling Malik’s lungs.

Malik has been driving heavy trucks for more than a decade, hauling cargo across Ghana’s deteriorating highways. At 48, he says he can feel his body breaking down along with the roads. Once a high school athlete, Malik now struggles to walk 100 meters without gasping for breath. The smoke from his own truck has become his slow poison.

“There’s no air conditioning, so when the smoke comes, it comes straight into the cab,” Malik says, speaking in Twi, refusing to let his photograph be taken with the soot-blackened interior visible behind him. “What can I do? Can you say you won’t breathe?”

His question captures a crisis unfolding across Ghana. While successive governments pledged to build a modern freight rail system that would shift cargo off the roads, the promises have never materialized. More than 800,000 medium and heavy-duty diesel-fuelled trucks now move 95 percent of the nation’s freight, creating an environmental and public health emergency that studies show claims thousands of Ghanaian lives every year and exposes millions more to dangerous levels of air and noise pollution.

According to the most recent study communities along major freight corridors inhale particulate matter and dangerous gases that trigger respiratory illness, cardiovascular disease, and premature death. Roads designed for passenger vehicles buckle under the weight of overloaded trucks, requiring constant, costly repairs.

Trucks on the Winkogo – Bolgatanga road [part of the N10]

Trucks on the Winkogo – Bolgatanga road [part of the N10]

The trajectory is clear: with freight volumes growing at more than five percent annually, Ghana will have even more trucks on the roads, generating more emissions, damaging infrastructure faster, and exposing millions more people to dangerous pollution levels.

A truck with thick black smoke as it moves along the Bolgatanga-Paga Highway

A truck with thick black smoke as it moves along the Bolgatanga-Paga Highway

A Costly But Essential National Investment

The case for freight rail over long-haul trucking is unambiguous, according to international research and Ghana’s own transport experts. Studies show that heavy diesel trucks emit more than seven times the greenhouse gases (toxic gases driving climate change and air pollution) as rail for the same cargo. Research from the United States found that shifting freight from truck to rail can reduce greenhouse gas emissions by up to 75 percent.

There is no current research on the level of air pollution caused by heavy vehicles. The last study, in 2015, found air quality along major corridors degraded by nearly 60 percent between 1995 and 2015, driven largely by heavy truck traffic. Experts say the pollution is likely far worse now. Latest figures show that 32,000 Ghanaians died prematurely in 2023 because of air pollution and millions more are sickened. Transportation is the biggest contributor.

Dr Gameli Hodoli, an air pollution scientist and lecturer at the University of Environment and Sustainable Development, has documented the health crisis firsthand. His monitoring of urban centres like Cape Coast and Accra shows pollution spikes twice daily, once in the morning and again in the evening, corresponding to rush hours when trucks mix with passenger vehicles, motorcycles, and pedestrians.

Dr. Collins Hodoli. Air pollution Scientist

Dr. Collins Hodoli. Air pollution Scientist

“Children under age five in Ghana are exposed to air pollution levels 100 times more than their counterparts in high-income countries,” Dr Hodoli says referring to PM₂.₅ – the fine particulate matter small enough to penetrate deep into the lungs and bloodstream. “Studies have linked exposure to PM₂.₅ to diminished neurodevelopment, asthma, and respiratory disorders.”

“A shift in domestic cargo transport from road freight to rail will significantly reduce emissions and congestion in urban centres in the long term. I am often baffled by the fact that our transportation infrastructure is solely for vehicular movements without considerations for alternatives.”

The Promise That Faded

Ghana once had a functioning rail network. Over 100 years ago, British colonisers constructed the first railway line connecting the coastal town of Sekondi with the gold-rich enclaves of Obuasi and Tarkwa. Not long after independence in 1957, Ghana initiated a robust railway system. Until the 1970s, trains carried minerals from Takoradi, cocoa from Kumasi, and goods between Accra and Tema. Ghana’s railway was recognized as one of the best on the continent according to a 2022 paper by researchers at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology.

The advantage was substantial: a single freight train could haul what required 50 to 100 trucks, with dramatically lower emissions. But decades of neglect and underinvestment caused the system to collapse. By the 2000s, freight rail had virtually disappeared.

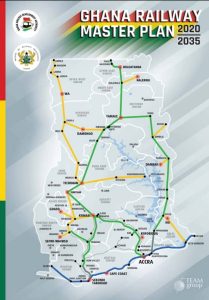

From 2013 successive governments promised to rebuild the system. Ghana developed an ambitious Railway Master Plan envisioning approximately 4,000 kilometres of rail lines to be built in phases, ferrying newly discovered minerals from the Eastern, Western and Central corridors to the ports of Tema and Takoradi. It was to extend north to Burkina Faso through the Upper East Region. The plan promised to shift a substantial portion of long-haul cargo from trucks to rail by 2020, dramatically reducing road congestion, infrastructure damage, and pollution in towns along the routes. Nothing happened.

Ghana’s railway revival, launched again with high hopes in 2017, under then-president Nana Akufo-Addo created a Ministry of Railway Development, signed contracts and ordered feasibility studies, with then–Finance Minister Ken Ofori-Atta calling it the country’s biggest infrastructure investment since independence.

But most of the projects never moved beyond the planning stage. Rising debt, difficulty securing financing and later economic shocks, including COVID-19 and the debt crisis, slowed progress. In 2023, the government closed the standalone railway ministry and moved its work to the Transport Ministry, leaving Ghana’s rail system largely unchanged.

President John Dramani Mahama, who returned to office in January 2025, has promised to revive Ghana’s rail sector. In its 2024 manifesto, his National Democratic Congress pledged to rehabilitate the Western Corridor line with private partners and build a new line from Sekondi-Takoradi through several regions to Hamile in the Upper West. Speaking at the Ghana Transport and Logistics Fair in October, Mahama said his government would modernize Ghana’s rail, road, maritime and aviation systems to improve the movement of people and goods. He has also directed the Transport Ministry to extend the railway from Tema Port to the Dawa Industrial Enclave to support freight traffic as work continues on the Mpakadan Inland Port.

Despite these commitments, rail transport remains marginal. By 2025, freight carried by rail accounts for less than 1 percent of Ghana’s cargo. The Takoradi–Kumasi line, once key for moving minerals and farm produce, is largely out of use. Much of the promised modern rail network exists only in incomplete and disconnected sections.

The Ghana Railway Authority did not respond to a request for comment by deadline. A senior engineer agreed to speak on the condition of anonymity as they had not been given permission to speak to the media. The Ghana Railway Company currently operates under an internally generated fund model, which chronically starves the system of capital for maintenance, workforce development, and asset replacement.

“International experience from European railways demonstrates that sustainable freight rail systems require direct government financial responsibility,” says the engineer, pointing to European Public Service Obligation models where governments take full fiscal responsibility for rail operations. “When governments do this, finances are managed transparently, capital is allocated systematically, and employees receive equipment and resources consistently.”

“If we had an efficient rail system, most of this cargo would move by rail,” the engineer said. “Policy documents envisaged rail eventually handling up to about 60 percent of solid and liquid bulk cargo between the ports and the interior—a major shift away from the current truck-dominated system.”

Corridor Communities Bear the Burden

For residents along Ghana’s major freight routes, the pollution isn’t abstract data—it’s a daily assault on health and livelihood.

Rihanna Lukeman runs a food container along the Bolgatanga-Tamale Highway, next to the Axle Weight Load Station where heavy trucks queue constantly. Each day begins at 10 a.m. with sweeping, an endless battle against dust kicked up by truck traffic on the deteriorating road. Throughout the day, she and her workers clean multiple times before closing around 7 p.m., but the dust never stops.

Ms. Lukeman’s foodstall

Ms. Lukeman’s foodstall

Neither does the smoke. Trucks idling at the weigh station belch diesel fumes that mingle with road dust, creating a toxic haze that clings to everything – the food she sells, the customers who rarely sit to eat, her own lungs.

“Customers don’t come because they can’t sit to eat because of the dust,” Rihanna says with hoarse voice. “I have catarrh that doesn’t go because of the dust. My voice isn’t clear. I have been going to the hospital but it doesn’t get better.”

She isn’t alone. Benedicta Agambila, another food vendor on the same highway, wears a nose mask constantly. She had envisioned her business attracting travellers during evening hours—people stopping for dinner breaks on long journeys. Instead, customers leave quickly, unable to tolerate the dust and exhaust.

Dr Emmanuel Anafo, a physician specialist at the Upper East Regional Hospital, sees the health consequences daily. He explains how carbon monoxide from diesel engines binds to haemoglobin in red blood cells, displacing oxygen and starving organs of the fuel they need to function.

Dr. Emmanuel Anafo, Physician Specialist

Dr. Emmanuel Anafo, Physician Specialist

“Usually when you breathe in, oxygen binds to our red blood cells,” Dr Anafo explains. “But when you have excessive exposure to carbon monoxide, it binds competitively to the haemoglobin more than oxygen. It will first affect your brain—you become confused, agitated, and you can lose consciousness. The heart also needs oxygen, so you can start getting cardiac arrhythmias. Your muscles won’t get the energy they need to move.”

For people like Rihanna, Benedicta, and Abdul Malik, this exposure is not a one-time event but a daily reality. Dr Anafo links years of breathing diesel fumes and traffic-related air pollution to chronic respiratory disease, long-term cardiovascular damage, and a higher risk of premature death, especially among those who live and work along Ghana’s busiest freight corridors.

Trucks along headed towards Wulugu on the Bolgatanga – Tamale Highway

Trucks along headed towards Wulugu on the Bolgatanga – Tamale Highway

How Roads Fail Under Freight

The damage extends beyond human health to Ghana’s infrastructure itself.

Ing. Peter Amoako, a roads engineer with the Urban Roads Department, explains that every road in Ghana undergoes pavement design based on expected traffic loads and projected growth rates over a 25- to 30-year design life. Engineers calculate the equivalent standard axle load that the pavement must withstand, mixing materials in precise proportions to handle the stress.

“When we have overloaded freight vehicles,” Ing. Amoako says, “it means if it’s more than the designed axle load, certainly it will put a lot of stress on the pavements. This will create defects—cracks and potholes. When these potholes develop, water seeps into the pavement, and by the time you realize, these minor defects have worsened the condition of the road.”

An 18 wheeler truck loaded with a mining truck

An 18 wheeler truck loaded with a mining truck

As road surfaces break down, vehicles are forced to brake, accelerate, and rattle over damaged sections, generating more dust, higher noise levels, and increased exhaust emissions that collectively worsen air pollution in surrounding communities.

He points to the Takoradi–Tarkwa–Huni Valley corridor. What was once a 45-minute journey now takes at least 90 minutes due to pavement failure from heavy truck traffic carrying minerals and bulk goods that were supposed to move by rail. The Western Rail Line, designed specifically for this freight, remains largely non-functional.

In towns like Bolgatanga, Tamale, Techiman, and Ejura, long-haul trucks create what Ing. Amoako calls a “mixed traffic stream”—heavy freight vehicles sharing narrow roads with motorcycles, bicycles, pedestrians, and passenger vehicles. The vulnerable road users, those on foot or two wheels, bear the greatest risk of air pollution by the trucks. But without functional rail alternatives, trucks have no choice but to use existing highways.

Weak Urban Planning Fuels Inequality Leaving Poor to Suffer the Most

“The proliferation of heavy-truck freight traffic is exerting considerable pressure on air quality and urban liveability,” says Dr Luis Kusi Frimpong, an urban geographer at the University of Environment and Sustainable Development.

Dr Luis Kusi Frimpong, an Urban Geographer

Dr Luis Kusi Frimpong, an Urban Geographer

He notes that informal settlements and high-density neighbourhoods typically sit along major transport corridors, lacking protective buffers like green spaces. Over time, this entrenches environmental injustice: poorer communities shoulder the health costs of freight movement while wealthier areas benefit from the goods being transported.

A functional freight rail network would fundamentally alter this pattern, Dr Frimpong argues. By diverting long-haul cargo from urban roads, rail would ease congestion, improve air quality, and enhance safety for pedestrians and public transport users. Rail freight hubs could stimulate more compact, organized industrial development rather than the current dispersed, road-dependent pattern.

“Moving forward, deliberate policy shifts are needed to recognize freight rail as a core component of sustainable urban development,” Dr Frimpong says. “This includes integrating freight considerations into metropolitan structure plans and aligning land-use planning with logistics development around rail corridors.”

Experts Say Ghana Must Fight Air Pollution and Climate Change Together

Experts agree: climate change and air pollution are linked. The emissions that cause climate change cause air pollution. Though Ghana’s contribution to climate change is tiny, it has signed up to Paris Agreement and made commitments to curb emissions in order to receive support to help its people adapt to climate change.

“This requires a consolidated policy to tackle them together. Currently, Ghana lacks a clear plan on emissions reduction,” says Dr Hodoli says, contrasting this with the United States’ Clean Air Act, which sets specific reduction targets based on scientific evidence. (The Trump administration has dramatically scaled back Clean Air Act regulations in the last year.) “To my mind, a clear plan for a clean environment will provide the ‘how’ and ‘why’ Ghana should define pathways for emissions reduction.”

Experts urge experts urge drivers, passengers and pedestrians to demand their political leaders make a major rail system a priority. In the meantime, they say people should do all they can to protect themselves. The first priority should be to wear N95 nosemasks. After that they should seal vehicles, close windows and repair air conditioning units. And access non-polluted air as often as possible.

This story was a collaboration with New Narratives. Funding was provided by the Clean Air Fund. The donor had no say in the story’s content.

Ms. Lukeman’s foodstall

Ms. Lukeman’s foodstall Ing. Peter Amoako

Ing. Peter Amoako